Our Simple and Scalable 100% Github Workflow (0% Jira)

December 7, 2015, by jeremyFor better or worse, I am old enough to remember the bugzilla days. Days when we had to do obscure trigonometry between severity and priority to understand which issue should come first; days when only the nerdiest of the nerds could make sense of it all, and others had to quietly hide their confusion for fear of being outcast; days when making simple queries was more complex than making complex ones, and days when we convinced ourselves that real software development process required management tools with more knobs than doors, just in case.

Fast forward 20 years, and we now have a slew of new issue-tracking tools with almost as many different approaches, from the king-of-all-knobs, Jira, to the opinionated Pivotal Tracker, to the minimalistic and code-centric GitHub issue-tracking approach.

While the general consensus tends to favor “functionally rich” issue-tracking systems, such as Jira, to manage “real” software projects, our experience shows that what really maximizes the traction of a project is how close everybody is to the code rather than how sophisticated the project management tool is. In fact, we found that choosing a simpler but more integrated tool, such as Github, with a well-thought-out set of best practices can be a robust platform for a highly effective agile development.

Rather than going too much into the theory, here is our 100% Github-based agile development process.

Milestones & Drops

First, no matter the agile development process used (e.g., Scrum or Kanban), any software project has to have a plan (i.e., a roadmap) composed of a set of sequential milestones, usually defined by the business and product stakeholders, and some code deliveries, referred to in this article as “drops,” that partially or completely match an upcoming milestone.

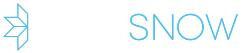

For a simple project, the base process will look like this:

-

Milestones are created in Github as such and follow the common alpha, beta, and dot versioning nomenclature, where the third digit typically corresponds to the patch release. Each milestone has a list of requirements and specifications, and all tickets (i.e., Github issues) are assigned milestones. Sometimes a “future” milestone is used to capture unscheduled ideas or features.

-

Drops are marching steps toward a milestone that is worth being looked at by some of the team members, such as a QA team or other product stakeholder. Drops are typically scheduled weekly, but they can be daily when approaching a milestone date. Once a drop matches a milestone at the desired quality, the release is made and distributed (e.g., deployed to the production server or published as an app).

In short, milestones represent the “what & when” defined by the business side, and drops are the code deliveries produced by engineering toward a milestone.

Here are a couple of important points about drops.

First, a drop is a build, but not all builds are drops, as builds tend to be generated daily or based on some code event such as a commit or pull request, whereas drops have a human decision factor that makes them worthwhile to look at. For example, when a drop is scheduled weekly on Tuesdays, developers will take extra care the day before, raising the drop quality and the effectiveness of its review.

Second, features are not scheduled by drops but prioritized by milestones and progressively implemented in drops. Often, a bigger milestone’s features will be split into smaller incremental tickets that can be delivered gradually, giving the engineering an opportunity to better manage the complexity and giving the product team a better appreciation of the cost of a feature and its possible tradeoff. The end result of this approach is better collective learning about the overall team velocity rather than over-planning of a single link of the chain.

Note 1) We like to use the term “ticket” rather than “issue” because it is a more general and positive description of a unit of work.

Note 2) While the dot versioning might sound old-fashioned and not sprint friendly, it is actually a very logical and natural nomenclature that both business and product teams can relate to, and this in itself has high value.

Branches & Tags

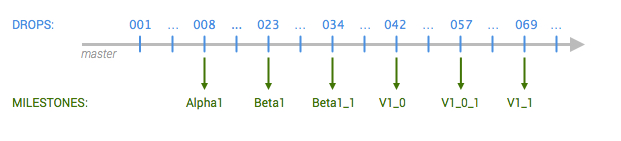

In an SAAS/cloud application scenario, we keep a “master” branch at “prod + 1” from production where “prod” is what is deployed in production. This is a great forcing factor to keep the master branch clean and conservative, as it should be.

As the product and team mature, the need for different tracks will emerge, especially when anticipating some patch releases. In this case, we keep the master branch as the “prod + 1” branch, which will be for the patch releases, and create future or feature branches that will have their own sequential numbers.

To keep everything neat and organized, all drop numbers are padded consistently, and each drop gets tagged with the branch name when not master branch. Regularly merging the “parent branch” to the future/feature branch is a simple way to avoid branch drifting, which can quickly become unproductive. Most of the time, the parent branch will be master, but with a bigger team, a “feature branch” can “inherit” a “future” branch. One rule of thumb with Git is that it is often better to branch earlier—in the case of optional features, for example—and merge later, rather than trying to split things after the fact.

Note 1) We usually pad the master branch drop number by three (e.g., 002 or 045) and the feature or future branch by two (which is plenty given their short lifespan).

Note 2) We also like to the version in the code, often as Java static variable (AppConfig.VERSION) Java static variable, which will update to “DROP-[n+1]-SNAPSHOT” in between drops. Also, we make sure that each version update has its own commit with the version, which allows us to see the version history with a simple “git log.”

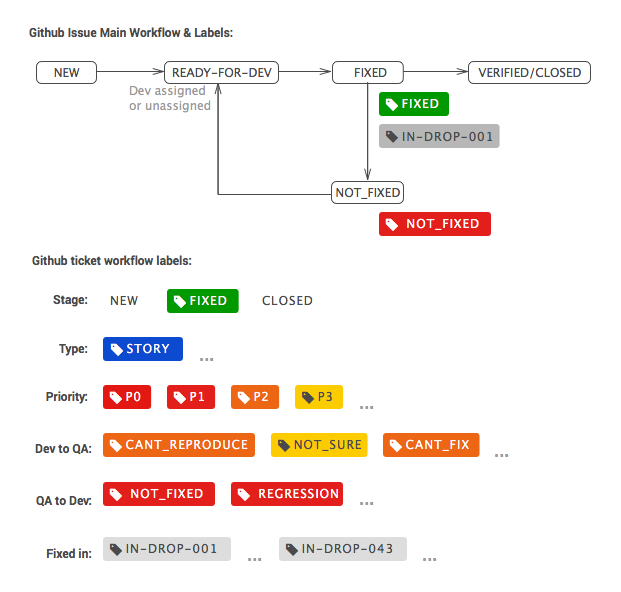

Workflow & Labels

Now that the tracks are set, the next step is to define how the work units roll onto them, and this is where the Github label system really shines.

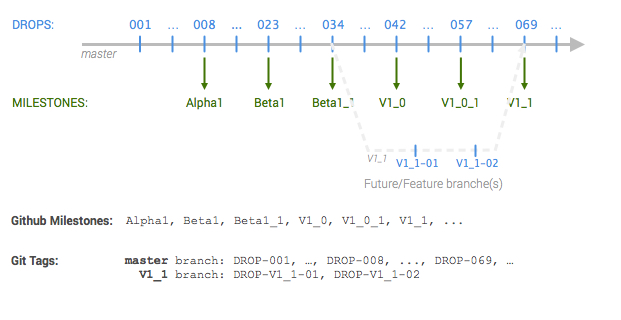

First, let’s define the simplest possible workflow.

| NEW | A ticket is entered into the system as a Github issue. |

| READY-FOR-DEV | As a general rule, unassigned tickets will get picked up by development, whereas tickets that are assigned to no developer will be considered “still in specification phase.” This simple rule allows the product and QA team to send items to the development queue without having to know which developer is the most equipped to work on it. |

| NEW | A ticket is entered into the system as a Github issue. |

| FIXED | Once the ticket is fixed, the developer will add the label FIXED, the label of the upcoming drop (IN-DROP-…), and assign it back to the reporter (usually the QA engineer or designer). |

| NOT_FIXED | Once a drop is made, the ticket reporter verifies the ticket; if it is not fixed, he/she removes the FIXED label, adds the NOT_FIXED label, and assigns it back to the developer. CLOSED Once the ticket passes the test, the reporter just closes it. Note that if the ticket has required more than one drop, we will have more than one IN-DROP-… label, which is very useful information. |

An important nuance of this workflow is that it is mostly label driven rather than “field” driven like other issue tracking systems. While this might sound insignificant at first, with Github’s great label implementations and a little bit of discipline, this minimalistic approach scales very well with the project and team.

For example, at BriteSnow, we usually start projects with the following categorized labels:

Some labels reflect tickets’ properties, such as the priority labels, while others are flow centric, such as the Dev to QA and QA to Dev ones, and as the project and team mature, we will add more labels and even categories as needed.

So, what makes Github labels so great?

After all, most issue tracking systems have some sort of label support as well. The key difference is that most issue tracking systems have implemented labels as an afterthought or a minor side feature, as most of the ticket states are managed by many custom fields (aka knobs). However, Github’s minimalistic three-knob approach (i.e., Assignee, Milestone, and Label) has been a forceful factor in making labels the mother of all knobs, and consequently it is very efficient and pervasive throughout the application.

Here are some of the specifics of what make Github labels so great:

- Github labels are extremely simple to create and assign, making them effortless.

- Github labels are displayed nicely and prominently in all ticket lists, and their custom color makes them even more visually informative.

- Github keeps all label assignments and removal history in the ticket activity stream, in-line with the comments, which gives tremendous insight in a ticket history.

- Github issue filtering is simple, powerful and best of all, fully URL addressable (no more save before share). After any filter you can copy paste the URL and share it on wiki pages or email reporting. No more building list, sharing links that get re-written each time you access them or dealing with the URL sub-optimized lifecycle.

The point is not to picture Github as the perfect end-all-be-all tool, but rather its robust label implementation lends itself well to building a simple and scalable label-driven workflow.

Note 1) For priorities, we usually use the following nomenclature: P0 = Blocker, P1 = Must have, P2 = Should have, P3 = Nice to have. Tickets without priorities will be done as time allows.

Note 2) We also like to keep track of when a ticket has supposedly been fixed (this will be set by the developers), as in an “IN-DROP-….” tag following the tagging nomenclature.

One Pitfall - Github Requires Push Privilege to Assign Label

There is one pitfall in Github’s label implementation, which can be frustrating at times. Somehow, the Github development team decides to tie issue-tracking privileges (such as assigning/removing labels) with the git repository read and write ones, and as a result requires push privilege to assign/remove labels. While this might not be a big problem for many development teams, in our case, it does add a little bit of friction as we like to grant the push privilege to the master repository only to the dev lead(s).

This issue is not strictly blocking for us, and Github’s benefits still outweigh this inconvenience; however, I really hope that Github will decouple those privileges as, in my experience, they are completely unrelated. One of Github’s “recommended” workarounds is to create a separate repository for issue tracking, but that would remove most if not all of the benefits of a tight source control and issue tracking system.

Conclusion

To summarize, a tool is just a mean and not a goal, and our experienced shown us that simpler tooling helps keep everybody outcome centric rather than tool centric. Endless tooling discussions in development meetings (.e.g., priority vs severity) are usually symptoms of tooling over-heating and the best way to cool the system down is to get back to the strict minimum and grow organically from there.

That being said, it is definitely possible to use Jira the “simple way,” (as we do with some of our clients), it just takes some extra discipline to resist the temptation to use all of those shiny knobs, and while Github is a great developer tool and a great base code platform, there is definitely room for improvement and extension, especially from a planing and documentation perspective, but this will be the topic for later.

Regardless of the tool used, if there is one thing to remember from this post, it is that the closest everybody is to the code, the more traction a project will get. While it will take a little effort for everybody to adapt to each other’s terminologies and tools at first, once realized, friction will be greatly minimized and throughput maximized.

If you appreciated this article, retweet and share are greatly appreciated.

Here is the full infographic of our github process: